UN Committee states that children must not witness violence towards animals

The UN Committee for the Rights of the Child has stated that states must protect children ‘from all forms of physical and psychological violence’ including ‘violence inflicted on animals’. This includes culling of free-roaming dogs and cats in public.Read More

ICAM condems inhumane culling of free-roaming dogs in Morocco

As the hosts of the 4th International Conference on Dog and Cat Population Management, ICAM feels compelled to publicly state its opposition to the ongoing inhumane culling of free-roaming dogs in Morocco.Read More

Global veterinary body gives support for humane DPM

The OIE adopts an updated chapter 7.7, including changing the title to ‘dog population management’, welcoming a systems-based approach to managing dogs humanely. Read More

Jaipur ABC costs greatly outweighed by benefits in dog bites and human rabies deaths

An economic analysis of dog population management (DPM) is a rare and valuable commentary. So when ICAM read Andrew Larkin’s peer-review publication reporting a net benefit of many millions USD resulting from Help In Suffering’s DPM work in Jaipur, we felt excited to share these findings with the wider DPM field.Read More

Rethinking population control through changing food resources

ICAM explains the reasoning behind their position statement on dog and cat population management and changing the availability of food resources.Read More

Mars Petcare launches their State of Pet Homelessness Index

Read why we welcome this contribution to the understanding of dog and cat population management, and what we urge as next steps following this important benchmark.Read More

ICAM stands in solidarity with Ukraine’s people and animals

Read our statement of support for the Ukrainian people and their animals and find links to our member’s response pages.Read More

ICAM calls for One Health action this World Rabies Day

This World Rabies Day, the International Companion Animal Management Coalition urges governments around the world to adopt and strengthen the One Health approach with a clear and unmitigated focus on mass dog vaccination for eliminating rabies by 2030 – the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal target that all member states signed up to.

Every year 59,000 people die from rabies and millions of dogs are inhumanely culled in a misguided attempt to stop the spread of rabies. We know that killing dogs does not stop the disease. Removal of dogs through culling or for consumption undermines rabies control efforts. Indiscriminate culling and removal of dogs inadvertently targets the more accessible vaccinated dogs and brings down vaccination coverage (the number of vaccinated dogs as a proportion of the total dog population). It destabilises the population leading to a younger population of rabies susceptible dogs and leads to public upset and resistance against rabies control. What works is mass dog vaccination – the only efficient and proven way to eliminate rabies.

Humane Dog Population Management (DPM) can further contribute to rabies control by reducing unwanted or unmanaged dogs and reducing population turnover, keeping vaccination coverage high and therefore achieving herd immunity (when enough of the population is resistant so the virus cannot spread and dies out) to protect dogs and people. DPM is important to sustain the gains of mass dog vaccination.

Efforts to eliminate rabies not only has an impact on bite cases and mortality, but also a psychological impact, changing perceptions of dogs from animals to be feared to companions. Therefore, by eliminating rabies through mass dog vaccination, animal welfare and the treatment of dogs will also improve in addition to the human health benefits.

The ongoing global COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the interconnect between animal, human, and environmental health. The significance of the One Health approach to address current and future challenge cannot be overstated – with multiple sectors and stakeholders stepping outside their silos to collaborate towards common health goals. Rabies elimination is the perfect example of One Health in action – a focus on dog health that saves the lives of people and the enormous financial burden of this disease.

Rabies, despite being one of oldest known zoonotic diseases, continues to be one of the major public health problems in around 150 countries around the world. This is the disease that impacts the poorest countries and the poorest communities within them. Truly a disease of poverty that needs to be consigned to history books.

Search for an event or register your own World Rabies Day event on the GARC website.

Join the webinar on Monday September 28

Join the WSAVA’s 2 part webinar on September 28 to mark this year’s World Rabies Day. Bringing together stakeholders and experts, including the OIE, GARC and World Animal Protection to discuss the importance of humane management and animal welfare in the global fight against rabies.

Read ‘All eyes on dogs’

Read World Animal Protection’s ‘All eyes on dogs’ report on why dogs hold the key to rabies elimination. And what actions stakeholders must do to achieve the goal of ending human rabies by 2030.

Download the report in English, Portuguese/Português, Spanish/Español, Thai/??? or Mandarin/???.

About International Companion Animal Management (ICAM) Coalition

ICAM supports the development and use of humane and effective companion animal population management worldwide. The coalition was formed in 2006 as a forum for discussion on global dog and cat management issues.

Our key goals are to:

- Share ideas and data

- Discuss issues relevant to population management and welfare

- Agree definitions and hence improve understanding

- Provide guidance as a collegial and cohesive group

Contact information: info@icam-coalition.org

Twitter: @ICAMCoalition

Infected not infectious: How dogs and cats have become the victims of COVID-19

Those of us who work with companion animals will be all too aware of zoonotic diseases. These are diseases that are passed between animals and people, including rabies. Using vaccination and deworming to prevent these diseases in dogs and cats, and therefore also protect people, is a constant drive within our work.

COVID-19 is different. There are competing hypotheses for where it originated, including transmission from animals (possibly bats or pangolins) to people, we may never know the truth. But since the original ‘case zero’ in Wuhan, China, the transmission appears to have been entirely person to person. Except we have seen the odd rare case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in companion animals. Importantly, all these cases suggest the transmission was from an owner to their pet and not the other way; the person is sick, and some days later their animal shows similar signs or is tested positive during quarantine by public health officials. ‘Reverse zoonosis’ is a relatively rarely used term in companion animals but may be suitable with COVID-19. This is where an animal is the victim of a disease hosted by the human population; it has become infected, but it is not infectious.

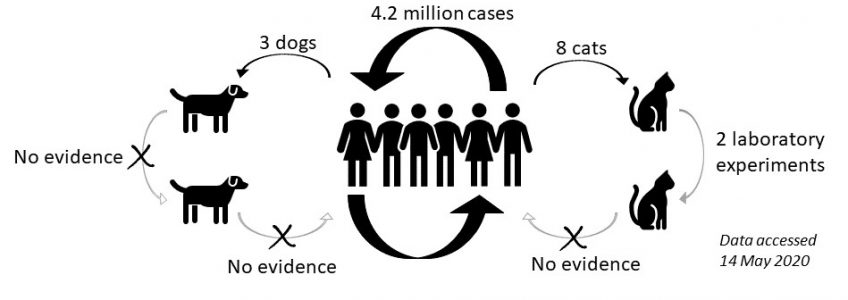

Infected: Can dogs and cats be infected by SARS-CoV-2?

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic we have seen a number of positive cases in companion animals (see our blog on why testing in companion animals should be limited). But equally as important, are the negative results. The following is a summary of both. See the footnote for an explanation of the different diagnostic tests used¹:

Pets in homes with COVID-19 tested using RT-PCR:

Positive cases

|

Negative

|

Studies of infection in real-world samples:

Positive

|

Negative

|

Studies of infection in the laboratory:

Studying infection in a laboratory involves inoculation of animals with virus. Two laboratory-based experimental studies have produced the following results; Shi et al (2020) in China and Halfmann et al (2020) in USA/Japan.

Positive

|

Positive and negative

|

These studies involved placing large doses of virus onto susceptible tissues deep inside nasal passages, mouths and eyes; this may be very different to the viral loads and exposure experienced in the real-world. The type of laboratory animals used and the way they are kept may also contribute to reduced immunity. Hence, ICAM advises caution in applying the results of such experimental studies to real-world disease control. These studies may be more suited to comparing responses between species or individuals within the confines of the study.

Infectious: Can dogs and cats transmit SARS-CoV-2 to other dogs and cats?

There is no real-world evidence of transmission between animals, on the contrary, some of the positive cases mentioned previously lived with other animals that tested negative. However, there is evidence of transmission between cats from the two laboratory-based studies mentioned previously (Shi et al 2020 and Halfmann et al 2020). These studies exposed naive animals (animals that had not been infected with virus) to inoculated animals to see if these naive animals would then ‘catch’ the virus.

- Shi et al. 6 pairs of inoculated and exposed cats were housed in neighbouring cages. The exposed cats in 2 pairs had positive results for PCR and antibodies, the other 4 exposed cats were negative. The same scenario with 2 pairs of dogs showed the exposed dogs had no positive test results. This suggests that transmission between dogs is not possible, but transmission between cats might be possible.

- Halfmann et al repeated this study but just with 3 pairs of cats who were co-housed in small cages. They found all 3 exposed cats became infected. None of the cats showed symptoms and there was no evidence of viral shedding after 5 days.

As described above, these laboratory-based studies have limitations when extrapolating to real-world disease control. In addition to concerns about viral loads and immune system health, these pairs of cats were kept in constant close proximity in small cages. ICAM believes these factors in experimental studies combine to increase the chances of infection far higher than would occur in the real-world between pets or roaming animals.

Negative test results from real-world infections also provide some evidence that transmission between animals may not be occurring:

- The German Shepherd in Hong Kong that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 also lived with a mixed-breed dog that repeatedly tested negative.

- The cat in New York, USA from a COVID-19 home lived with another cat that tested negative.

- The Pug in North Carolina, USA lived with another dog and cat, neither tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

- The cat in Germany lived in a retirement home with her owner who died of COVID-19, two other cats that lived in the same home tested negative.

In each of these real-world scenarios is a test of potential transmission between animals AND from people to animals, as they were all in the same household with people who were sick with COVID-19. That transmission did not occur is evidence that sick owners infecting their pet is not inevitable, it appears to be very rare. It also suggests transmission is not occurring between animals.

Infectious: Can dogs and cats transmit SARS-CoV-2 to people?

“Currently, there is no evidence that animals are playing a significant epidemiological role in the spread of human infections with SARS-CoV-2.” OIE. Evidence of transmission from dogs or cats to people would require clarity on two factors; timing and other transmission routes. A person would need to become sick with COVID-19 after their dog or cat had shown signs of infection AND all other possible routes of transmission from people would need to be excluded. Because they are in contact with many more dogs and cats than most people, veterinarians and shelter workers would be most at risk for this kind of transmission. Thankfully, there appears to be no greater prevalence of COVID-19 in these workforces.

With over 4 million human cases worldwide we have an abundance of complex, uncontrolled but undeniably valuable epidemiological evidence about transmission. The extremely small number of infections from people to dogs and cats, and the lack of any examples of transmission to people, is meaningful. Dogs and cats are not playing a role in transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to people. These companion animals are the victims of this reverse zoonosis; they are (rarely) infected but not infectious.

Footnote 1: What testing methods are available for companion animals?

In the majority of cases, the tests offered for companion animals will be RT-PCR tests for viral genetic material. The following explains this test and its limitations in more detail and two other tests that are being used for companion animals, usually in research contexts:

- RT-PCR: Uses oral, nasal or fecal/rectal samples. Amplifies available genetic material so is very sensitive. However, a positive test doesn’t prove the virus is live, just there is viral genetic material there, which can occur after live virus has been cleared or if there have been contamination of the animal or sample by viral particles. Need to show persistent positive RT-PCR results to show an active infection.

- Virus isolation: This attempts to culture (grow) live virus from swabs, so a positive result implies there is an active infection and there may be a chance of infectiousness, although this depends on viral ‘load’ (amount of virus) and closeness of contact.

- Serology: Uses blood samples to test for the presence of antibodies. A positive result proves there was infection at some point. However, antibodies are slow to become detectable, so not the best markers for active or acute infection.

Resources

- AVMA

- OIE

- Worms and Germs blog

About International Companion Animal Management (ICAM) Coalition

ICAM supports the development and use of humane and effective companion animal population management worldwide. The coalition was formed in 2006 as a forum for discussion on global dog and cat management issues.

Our key goals are to:

- Share ideas and data

- Discuss issues relevant to population management and welfare

- Agree definitions and hence improve understanding

- Provide guidance as a collegial and cohesive group

Contact information: info@icam-coalition.org

Twitter: @ICAMCoalition

Contagiados, pero sin capacidad de contagiar: Cómo los perros y los gatos se han convertido en víctimas del COVID-19

Los que trabajamos con animales de compañía sabemos perfectamente qué son las enfermedades zoonóticas. Estas son enfermedades que se transmiten entre animales y personas, por ejemplo, la rabia. La vacunación y la desparasitación para prevenir dichas enfermedades en perros y gatos—y, por lo tanto, para también proteger a las personas—es una preocupación constante en nuestro trabajo.

El COVID-19 es diferente. Existen hipótesis opuestas sobre dónde se originó, por ejemplo, el contagio de animales (posiblemente murciélagos o pangolines) a personas, pero puede que nunca sepamos la verdad. Sin embargo, desde el “paciente cero” original de Wuhan, China, pareciera ser que el contagio haya sido completamente de persona a persona. Como excepción, hemos visto el extraño caso de animales de compañía contagiados con SARS-CoV-2. Cabe señalar que todos estos casos indican que el contagio fue de un amo a su mascota y no al revés; la persona se enferma, y algunos días después, su mascota presenta síntomas similares o los funcionarios sanitarios públicos le hacen una prueba que da positivo. La “zoonosis inversa” es un término que rara vez se usa en los animales de compañía, pero podría aplicarse al COVID-19. Esta se produce cuando un animal es víctima de una enfermedad sufrida por la población humana; es contagiado, pero no tiene capacidad de contagiar.

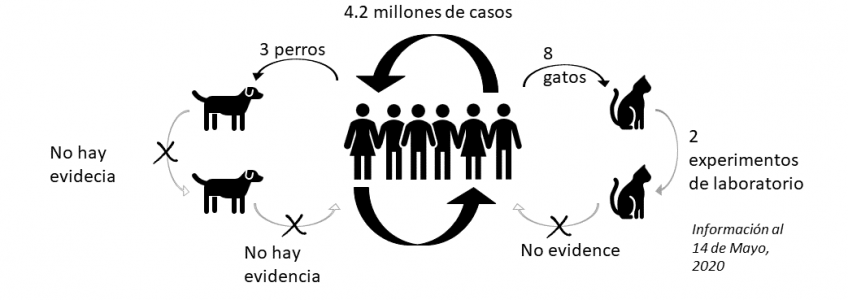

Contagios: ¿Los perros y los gatos pueden contagiarse de SARS-CoV-2?

Desde el brote de la pandemia de COVID-19, hemos visto varios casos positivos en animales de compañía (visite nuestro blog para saber por qué las pruebas en animales de compañía debieran ser limitadas). Sin embargo, los resultados negativos son igual de importantes. A continuación se presenta un resumen de ambos. En la nota al pie podrá ver una explicación de las distintas pruebas de diagnóstico utilizadas1:

Pets in homes with COVID-19 tested using RT-PCR:

Casos positivos

|

Casos negativos

|

Estudios de contagios en muestras del mundo real:

Positivos

|

Negativos

|

Estudios de contagios en laboratorio:

El estudio de los contagios en un laboratorio implica inocular el virus en los animales. Dos estudios experimentales llevado a cabo en laboratorio han producido los siguientes resultados: Shi et al (2020) en China y Halfmann et al (2020) en Estados Unidos/Japón.

Positivos

|

Positivos y negativos

|

Estos estudios colocan grandes dosis de virus en tejidos susceptibles ubicados en el fondo de las fosas nasales, lo cual podría diferir mucho de las cargas virales y de la exposición que se experimentan en el mundo real. El tipo de animales de laboratorio utilizados y la forma en como son mantenidos puede contribuir a una inmunidad reducida. Por ende, ICAM aconseja precaución a la hora de utilizar los resultados de estos experimentos en control de la enfermedad en el mundo real. Estos estudios sirven más para comparar respuestas entre especies o individuos dentro del marco del estudio.

Contagios: ¿Los perros y los gatos pueden contagiar el SARS-CoV-2 a otros perros y gatos?

No hay evidencia de transmisión entre animales, de hecho, algunos casos mencionados anteriormente que salieron positivos vivían con otros animales que salieron negativos. Sin embargo, sí hay evidencia de transmisión entre gatos en los dos estudios experimentales mencionados arriba de (Shi et al 2020) y Halfmann et al (2020). Estos estudios expusieron a los gatos no inoculados (que no había sido infectados con el virus) con gatos inoculados a ver si los no inoculados se enfermaban con el virus.

- Shi et al. Se colocaron animales inoculados (6) en jaulas adyacentes a las de animales no inoculados (6) para ver si dichos animales se contagiarían al ser expuestos a un animal inoculado. De los 6 pares de animales inoculados y expuestos, 2 pares de gatos dieron positivo a la PCR y a anticuerpos, y los otros 4 gatos expuestos dieron negativo. El mismo escenario con 2 pares de perros reveló que los perros expuestos no dieron resultados positivos. Esto sugiere que no es posible el contagio entre perros, pero que tal vez fuera posible entre gatos.

- Halfmann et all repite este estudio pero solo con 3 pares de gatos que se les puso en jaulas pequeñas. Los tres gatos expuestos se infectaron . Ninguno de los gatos presentó síntomas de la enfermedad y no había evidencia de diseminación del virus después de 5 días.

Como se describe más arriba, estos estudios hechos en laboratorio tienen sus limitaciones a la hora de extrapolar la información al control de la enfermedad en el mundo real. Además de las preocupaciones por las grandes dosis de virus y la salud inmunológica, estos gatos fueron mantenidos en proximidad y en jaulas pequeños. ICAM considera que estos factores que se combinan en eperimentos de laboratorio pueden aumentar la probabilidad de infección a mucho más de lo que se lograría en el mundo real con mascotas o entre animales deambulantes.

Los resultados negativos de los contagios del mundo real también entregan evidencia de que no existe contagio entre animales:

- El pastor alemán de Hong Kong que dio positivo a SARS-CoV-2 también vivía con un perro de raza mixta que dio negativo varias veces.

- El gato del hogar con COVID-19 de Nueva York, EE. UU. vivía con otro gato que dio negativo.

- El pug de Carolina del Norte, EE. UU. vivía con otro perro y otro gato, ninguno de los cuales dio positivo a SARS-CoV-2.

- El gato en Alemania vivía en una residencia de ancianos con su dueña que falleció de COVID-19, los otros dos gatos que vivían en el mismo hogar salieron negativos.

En cada uno de estos escenarios del mundo real, existe la posibilidad de contagio entre animales y de personas a animales, ya que todos se encontraban en el mismo hogar junto a personas infectadas de COVID-19. El hecho de no haberse transmitido la enfermedad constituye evidencia de que el contagio de los amos enfermos a sus mascotas no es inevitable, pero parece ser muy inusual. También indica que no existe contagio entre animales.

Contagios: ¿Los perros y los gatos pueden contagiar el SARS-CoV-2 a personas?

“Actualmente, no existe evidencia que indique que los animales cumplan un papel epidemiológico significativo en la propagación de contagios humanos de SARS-CoV-2” OIE. Respecto a la evidencia sobre el contagio de perros o gatos a personas, sería necesario aclarar dos factores: el tiempo y otras vías de transmisión. Una persona tendría que enfermarse de COVID-19 después de que su perro o gato haya presentado síntomas de contagio, y sería necesario excluir todas las otras vías posibles de contagio de personas. Puesto que están en contacto con muchos más perros y gatos que la mayoría de la gente, los veterinarios y los trabajadores de los refugios correrían el mayor riesgo ante este tipo de contagio. Por suerte, pareciera no haber una mayor prevalencia de COVID-19 en estos trabajadores.

Con casi 4 millones de casos humanos en todo el mundo, tenemos una gran cantidad de evidencia epidemiológica compleja, no controlada pero innegablemente valiosa sobre el contagio. La cantidad extremadamente baja de contagios de personas a perros y gatos, y la falta de ejemplos de contagio a personas, resulta significativa. Los perros y los gatos no cumplen un papel en el contagio del SARS-CoV-2 a personas. Estos animales de compañía son víctimas de la zoonosis inversa; son contagiados (rara vez), pero no tienen capacidad de contagiar.

Nota al pie 1: Métodos de detección para animales de compañía

En la mayoría de los casos, las pruebas para animales de compañía son pruebas de RT-PCR que buscan material viral genético. A continuación seexplica esta prueba y sus limitaciones en mayor detalle así como otras dos pruebas que están siendo usadas en animales de compañía, usualmente en el contexto de investigación:

- RT-PCR: Se utilizan muestras orales, nasales o fecales/rectales. Esta prueba amplifica el material genético disponible, por lo que es muy sensible. Sin embargo, un resultado positivo no indica que el virus está vivo, solo que existe material genético viral, el cual puede encontrarse después de haberse eliminado el virus o por contaminación del animal o de la muestra con partículas virales. Es necesario contar con resultados RT-PCR positivos persistentes para demostrar una infección activa.

- Aislamiento del virus: Se intenta cultivar el virus vivo a través de hisopos, por lo que un resultado positivo indica que existe una infección activa y que podría existir la probabilidad de contagiosidad, aunque esto depende de la “carga” viral (la cantidad de virus) y de la proximidad del contacto.

- Serología: Se utilizan muestras de sangre para detectar la presencia de anticuerpos. Un resultado positivo indica que en algún momento hubo una infección. Sin embargo, los anticuerpos tardan en ser detectables, por lo que no son los mejores indicadores de una infección activa o aguda.

Referencias y recursos

- AVMA

- OIE

- Worms and Germs blog

About International Companion Animal Management (ICAM) Coalition

ICAM supports the development and use of humane and effective companion animal population management worldwide. The coalition was formed in 2006 as a forum for discussion on global dog and cat management issues.

Our key goals are to:

- Share ideas and data

- Discuss issues relevant to population management and welfare

- Agree definitions and hence improve understanding

- Provide guidance as a collegial and cohesive group

Contact information: info@icam-coalition.org

Twitter: @ICAMCoalition