Those of us who work with companion animals will be all too aware of zoonotic diseases. These are diseases that are passed between animals and people, including rabies. Using vaccination and deworming to prevent these diseases in dogs and cats, and therefore also protect people, is a constant drive within our work.

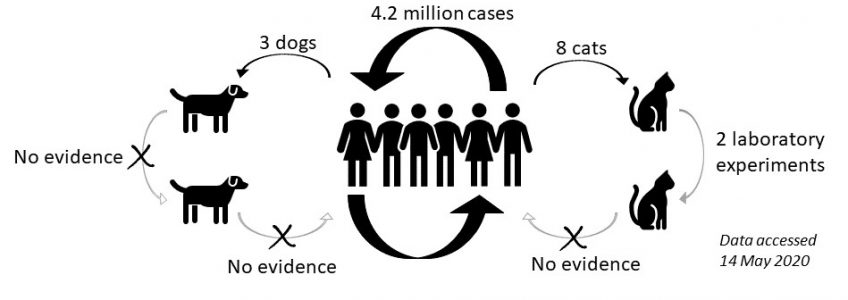

COVID-19 is different. There are competing hypotheses for where it originated, including transmission from animals (possibly bats or pangolins) to people, we may never know the truth. But since the original ‘case zero’ in Wuhan, China, the transmission appears to have been entirely person to person. Except we have seen the odd rare case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in companion animals. Importantly, all these cases suggest the transmission was from an owner to their pet and not the other way; the person is sick, and some days later their animal shows similar signs or is tested positive during quarantine by public health officials. ‘Reverse zoonosis’ is a relatively rarely used term in companion animals but may be suitable with COVID-19. This is where an animal is the victim of a disease hosted by the human population; it has become infected, but it is not infectious.

Infected: Can dogs and cats be infected by SARS-CoV-2?

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic we have seen a number of positive cases in companion animals (see our blog on why testing in companion animals should be limited). But equally as important, are the negative results. The following is a summary of both. See the footnote for an explanation of the different diagnostic tests used¹:

Pets in homes with COVID-19 tested using RT-PCR:

Positive cases

|

Negative

|

Studies of infection in real-world samples:

Positive

|

Negative

|

Studies of infection in the laboratory:

Studying infection in a laboratory involves inoculation of animals with virus. Two laboratory-based experimental studies have produced the following results; Shi et al (2020) in China and Halfmann et al (2020) in USA/Japan.

Positive

|

Positive and negative

|

These studies involved placing large doses of virus onto susceptible tissues deep inside nasal passages, mouths and eyes; this may be very different to the viral loads and exposure experienced in the real-world. The type of laboratory animals used and the way they are kept may also contribute to reduced immunity. Hence, ICAM advises caution in applying the results of such experimental studies to real-world disease control. These studies may be more suited to comparing responses between species or individuals within the confines of the study.

Infectious: Can dogs and cats transmit SARS-CoV-2 to other dogs and cats?

There is no real-world evidence of transmission between animals, on the contrary, some of the positive cases mentioned previously lived with other animals that tested negative. However, there is evidence of transmission between cats from the two laboratory-based studies mentioned previously (Shi et al 2020 and Halfmann et al 2020). These studies exposed naive animals (animals that had not been infected with virus) to inoculated animals to see if these naive animals would then ‘catch’ the virus.

- Shi et al. 6 pairs of inoculated and exposed cats were housed in neighbouring cages. The exposed cats in 2 pairs had positive results for PCR and antibodies, the other 4 exposed cats were negative. The same scenario with 2 pairs of dogs showed the exposed dogs had no positive test results. This suggests that transmission between dogs is not possible, but transmission between cats might be possible.

- Halfmann et al repeated this study but just with 3 pairs of cats who were co-housed in small cages. They found all 3 exposed cats became infected. None of the cats showed symptoms and there was no evidence of viral shedding after 5 days.

As described above, these laboratory-based studies have limitations when extrapolating to real-world disease control. In addition to concerns about viral loads and immune system health, these pairs of cats were kept in constant close proximity in small cages. ICAM believes these factors in experimental studies combine to increase the chances of infection far higher than would occur in the real-world between pets or roaming animals.

Negative test results from real-world infections also provide some evidence that transmission between animals may not be occurring:

- The German Shepherd in Hong Kong that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 also lived with a mixed-breed dog that repeatedly tested negative.

- The cat in New York, USA from a COVID-19 home lived with another cat that tested negative.

- The Pug in North Carolina, USA lived with another dog and cat, neither tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

- The cat in Germany lived in a retirement home with her owner who died of COVID-19, two other cats that lived in the same home tested negative.

In each of these real-world scenarios is a test of potential transmission between animals AND from people to animals, as they were all in the same household with people who were sick with COVID-19. That transmission did not occur is evidence that sick owners infecting their pet is not inevitable, it appears to be very rare. It also suggests transmission is not occurring between animals.

Infectious: Can dogs and cats transmit SARS-CoV-2 to people?

“Currently, there is no evidence that animals are playing a significant epidemiological role in the spread of human infections with SARS-CoV-2.” OIE. Evidence of transmission from dogs or cats to people would require clarity on two factors; timing and other transmission routes. A person would need to become sick with COVID-19 after their dog or cat had shown signs of infection AND all other possible routes of transmission from people would need to be excluded. Because they are in contact with many more dogs and cats than most people, veterinarians and shelter workers would be most at risk for this kind of transmission. Thankfully, there appears to be no greater prevalence of COVID-19 in these workforces.

With over 4 million human cases worldwide we have an abundance of complex, uncontrolled but undeniably valuable epidemiological evidence about transmission. The extremely small number of infections from people to dogs and cats, and the lack of any examples of transmission to people, is meaningful. Dogs and cats are not playing a role in transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to people. These companion animals are the victims of this reverse zoonosis; they are (rarely) infected but not infectious.

Footnote 1: What testing methods are available for companion animals?

In the majority of cases, the tests offered for companion animals will be RT-PCR tests for viral genetic material. The following explains this test and its limitations in more detail and two other tests that are being used for companion animals, usually in research contexts:

- RT-PCR: Uses oral, nasal or fecal/rectal samples. Amplifies available genetic material so is very sensitive. However, a positive test doesn’t prove the virus is live, just there is viral genetic material there, which can occur after live virus has been cleared or if there have been contamination of the animal or sample by viral particles. Need to show persistent positive RT-PCR results to show an active infection.

- Virus isolation: This attempts to culture (grow) live virus from swabs, so a positive result implies there is an active infection and there may be a chance of infectiousness, although this depends on viral ‘load’ (amount of virus) and closeness of contact.

- Serology: Uses blood samples to test for the presence of antibodies. A positive result proves there was infection at some point. However, antibodies are slow to become detectable, so not the best markers for active or acute infection.

Resources

- AVMA

- OIE

- Worms and Germs blog

About International Companion Animal Management (ICAM) Coalition

ICAM supports the development and use of humane and effective companion animal population management worldwide. The coalition was formed in 2006 as a forum for discussion on global dog and cat management issues.

Our key goals are to:

- Share ideas and data

- Discuss issues relevant to population management and welfare

- Agree definitions and hence improve understanding

- Provide guidance as a collegial and cohesive group

Contact information: info@icam-coalition.org

Twitter: @ICAMCoalition